By now, a lot of you have heard that the

Justice Department has jumped into the RIM v. NTP fray, worried silly that the outcome will disable the thousands of BlackBerry devices that the government relies on to conduct business.

What you may not know is that this is nothing new; the government has routinely had to step into patent battles to prevent the world from collapsing in on itself. In fact, it has had to do this for some of the most prominent inventions known to mankind. Let us start with the airplane.

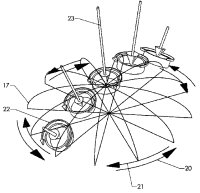

The Wright Brothers held several key patents on the airplane, and rightly so. Another inventor by the name of Glenn Curtiss (who coincidentally, was backed by Alexander Graham Bell) held patents on some additional aeronautic technology including ailerons, empennage, and a new engine. The Wrights wouldn't license their patents to Curtiss. Curtiss tried to build planes faster than the Wrights could litigate, and tried to invalidate some of their claims based on prior art from Langely and others. Years and years were wasted as these guys battled it out. Others also tried to build planes using the Wright innovations, but were largely stymied by the Wrights' demand for very high royalties. Meanwhile, Europe was progressing to flight at a rapid pace. Then WWI broke out.

Of the outcome to all this,

Idle Words writes:

The United States government finally put an end to the patent strife in 1917. Mindful of the impending war, it insisted that the rival parties form a patent pool - in effect, removing patent barriers to creating new airplane designs. Together with the war, the patent pool inspired a golden age of American aviation. The pool stayed in effect until 1975; companies who wanted to preserve a competitive advantage did so using trade secrets (such as Boeing's secret recipe for hanging jet engines under an airliner wing).

I believe that the Wright patent story drives home the intellectual bankruptcy of our patent system. The whole point of patents is supposed to be to encourage innovation, reward entrepreneurship, and make sure useful inventions get widely disseminated. But in this case (and in countless others, in other fields), the practical effect of patents turned out to be to hinder innovation - a patent war erupts, and ends up hamstringing truly innovative technologies, all without doing much for the inventors, who weren't motivated by money in the first place.

It's illuminating to point out that all three transformative technologies of the twentieth century - aviation, the automobile, and the digital computer - started off in patent battles and required a voluntary suspension of hostilities (a collective decision to ignore patents) before the technology could truly take hold.

I'd add that it isn't just these three seminal inventions - the

story of the modern steam engine and its patents' effect on derailing the Industrial Revolution is also very seminal. But back to Orville and Wilbur:

The Wright brothers won every patent case they fought, and it did them absolutely no good. The prospect of a fortune wasn't what motivated them to build an airplane, but ironically enough they could have made a fortune had they just passed on the litigation. In 1905, the Wrights were five years ahead of any potential competitor, and posessed a priceless body of practical knowledge. Their trade secrets and accumulated experience alone would have made them the leaders in the field, especially if they had teamed up with Curtiss. Instead, they got to watch heavily government-subsidized programs in Europe take the technical lead in airplane design as American aviation stagnated.

So, does the BlackBerry live or die? The government is asking for at least an exclusion for their workers, but are the government's 200,000 or so BlackBerry users enough justification, economically, for RIM to keep the network up? Idle Words asks the questions you should be pondering at this point:

if the patent system doesn't even work for the archetypal example - two inventors, working alone, who singlehandedly invent a major new technology - why do we keep it at all? Who really benefits, and who pays?

Update: Developments in the BlackBerry case.

This was the second in a series of stories about seminal inventions hindered by patents. Read Part I or Part III.